The Lindgren Group

Earthquake survivor supports the “last frontier”

It would be hard to make the case that anything good could ever come out of an earthquake. Especially an earthquake of enormous destructive power, like the Great Alaskan Earthquake of 1964, the most powerful tremor ever recorded in U.S. and North American history. Registering a magnitude of 9.2 on the Richter scale, it caused widespread desolation across the south-central part of the state. And yet, perhaps, if it wasn’t for that devastating natural disaster, the Port of Anchorage (POA) may never have become the economic engine that it is today, as well as one of Alaska’s most important maritime ports, responsible for supporting a vast majority of the Frontier State’s population with the goods they need to survive.

According to Stephen Ribuffo, Director for the Port of Anchorage, when the Port’s opening-day ribbon was cut in September, 1961, “it was a modest, little dock, with a pile-supported deck, and three small loading cranes to lift baskets and netting out of ships. That was the substance of the port when it opened for business.” And so it might have remained until one evening in March, three years later, when a four-minute-thirty-eight second tremor shook the earth, and the Great Alaska Quake began inflicting widespread damage throughout south-central Alaska and beyond.

Ribuffo continues the story: “It decimated the docks in Seward, and in Whittier, and in Valdez, and rendered them useless, because they’re all right there in the Gulf of Alaska and in Prince William Sound, and they were all susceptible to the tsunamis which wreaked all kinds of havoc as a consequence of the earthquake. The only dock in south-central Alaska that remained standing was the one in Anchorage. So, starting shortly thereafter, as part of the reconstruction efforts, the big container ships and cargo ships that used to go into Seward, began to come into Anchorage, instead.”

And so, a terrible accident that no one could have predicted, and certainly no one would have wanted, was the spark plug that ignited the economy of the last port standing and the city whose name it bears. “After that, it became the natural place to go,” Ribuffo relates. “And as Anchorage became the center for commerce, anyway – it’s the nexus for the Alaska Railroad; it’s where all the freight-forwarding companies have established their presence – it just seemed to make the best business sense for Anchorage to be the hub for the better part of all the water-borne freight that enters into south-central Alaska, as well.”

Soon, the POA became home to two major ocean carriers – Horizon Lines, Inc., and Totem Ocean Trailer Express (TOTE). “At the time it was SeaLand, which morphed into Horizon Lines, which is now Matson,” says Ribuffo. “They were the first. Our relationship with them began in the mid ‘60s, and it’s been a business relationship we’ve held, ever since. In the mid-‘70s, TOTE was added, and throughout that time the port grew, the dock grew, the large gantry-container-handling cranes were added, and TOTE, which has a roll on/roll off vessel configuration, added facilities with big ramps so that they could off-load and on-load their container ships by driving the containers on and off. And that’s how we grew from what was a modest, little facility to what it is and what we are, today.”

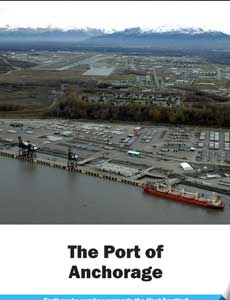

Today, the Port of Anchorage, which occupies approximately 220 acres, includes three general cargo terminals with 2,100 feet of dock face, with container, roll on/roll off, bulk cement and break bulk capabilities; two petroleum product terminals with 600 feet each of berthing space and four 2,000 bbl./hr.-product pipelines each; loose cement offloading capability via pneumatic pump and pipeline; two 30 ton and one 40 ton rail-mounted, electric cranes; and intermodal connections via rail, road, and air.

A half-century after the Great Quake, the Port of Anchorage can truly be called the Port of Alaska, as it has most definitely become its essential maritime hub. The cargo that passes through it supports roughly 85 percent of Alaska’s population of 760,000, in over 250 communities, supplying them with everything they eat, wear, drive, and put in their fuel tanks. “We’re the only intermodal port facility in the state,” says Ribuffo. “We support 75 percent of all the waterborne freight that enters south-central Alaska; 95 percent of all the refined petroleum; 100 percent of the fuel for Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson; and about 65 percent of what supports Ted Stevens International Airport. We’re also the ‘meat and potatoes’ guys with respect to groceries, and clothing, and refined petroleum products, all of which are consumed to sustain the population that we support.”

The POA is a municipal entity. “We’re a department of the City of Anchorage,” Ribuffo explains. “The Board of Directors is the Anchorage Assembly. All of our contracts, user agreements, and leases have to go through the Assembly for approval. We answer to them as a public sector entity. We’re considered an enterprise function, which means we have the responsibility of generating enough revenue to cover all of our own expenses. And, in addition to that, we pay a fee, in lieu of taxes, back to the city, every year, to help support city government.”

Ribuffo describes the way the Port generates its revenue: “Our two big business areas are containerized cargo – what we call vans, flats and containers – and refined petroleum. It’s approximately a 50/50 split between the two of those. We do have cement that’s part of our revenue base; we support a small number of cruise ships every year; and we do have one-off cargo deliveries that come and go, but, by and large, what you’ll see tied to the dock is a container ship or a petroleum barge or petroleum tanker.”

Once offloaded from the ships, cargo then gets dispersed throughout the state. “Incoming cargo gets distributed along the ‘rail belt’ – the tracks that run from the Seward/Whittier area, all the way up to Fairbanks,” Ribuffo says. “It’s a north/south configuration. It doesn’t go east and west. Anchorage is where the Alaska Railroad’s hub is; their rail center is less than three quarters of a mile from the Port. So, we’re co-located at the heart of the railroad’s operation.” Other parts of the state are serviced by truck, and some, especially the far-flung rural communities, by small plane. And in contrast with many other maritime ports, very little material goes out on POA ships. “They leave with containers, but about 80 percent of those containers are empty. No raw materials go out of this Port and there is no real industrial base that creates anything to export,” says Ribuffo.

The POA is a landlord port. It charges user fees for real estate and dock use. In turn, the Port is responsible for maintenance, management, and upkeep. And because the existing marine terminals are suffering from severe corrosion, the POA is embarking upon a modernization program to ensure infrastructure sturdiness as well as to accommodate expected growth in its core business lines over a 75-year life cycle. The project will replace two general cargo terminals and two petroleum terminals, while improving seismic resilience of the entire facility.

The modernization project should be complete within the next nine to ten years. It will rebuild port facilities, but it won’t be expanding them, since, according to Ribuffo, the POA’s current utilization rate is only at 40 percent capacity. “We can absorb more business without adding more infrastructure,” he says. “You don’t have to build more port. But we do need to have a port that will be standing here.”

“This modernization effort is important to us,” he continues, “because we have a facility which is now 54, going on 55 years old. And there’s quite a corrosion problem on the piles that support the dock. We invest, annually, in doing repairs on the worst of the piles – we can afford to do about a hundred a year to stay on top of the corrosion problem. But it does nothing to give us any structural integrity enough to survive another earthquake that might be of a magnitude of the ’64 earthquake. If another earthquake like that happened here, today, I don’t know what kind of shape this Port would be in, because of its age. So it’s important for us to replace the docks with something designed and built to current specifications that provides us a little better access to deeper water and provides our ocean carriers with a more modern infrastructure to make them more efficient.”

Helping to make its tenants more efficient is a bedrock principle of the POA. While it is the responsibility of the ocean lines, themselves, to grow their own businesses, and pay for their own upgrades and expansions, according to Ribuffo, “We need to be a ‘force multiplier.’ We need to provide a facility that makes these ocean carriers more competitive, efficient, available, and safe. And that puts the onus on us to keep the costs of operating here, down, so that the price points they can offer are more competitive. But we can’t plan a port in a vacuum. The tenants are involved in the design process, every day. If we’re not matching their needs, we’re making a mistake because these are the guys that support 80-plus percent of the population of the state. We can ill-afford to build something that they can’t use. We collaborate so that we’re not working at cross purposes.”

In addition to maintaining its core business while modernizing its docks, the POA also serves as one of 23 Department of Defense (DOD) designated National Strategic Ports. “What that means,” says Ribuffo, “is that we have an obligation to the Department of Defense to support their mission with marine facilities, as required. There’s a big military presence in the State of Alaska – our nearest neighbor to the east is Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson. The 4th Airborne Brigade Combat Team of the 25th Infantry Division is housed there. When they deploy, all their equipment comes down here to the Port, and when they redeploy, it does the same thing in reverse. We’re also connected, by rail, to Fort Wainwright, which is outside of Fairbanks, Alaska, and home to the 1st Striker Brigade Combat Team of the 25th Infantry Division. And any time those guys deploy, all of their rolling stock and containerized cargo goes on flat cars and it all gets moved down here to this Port and it goes out by water. So we have a responsibility to be supportive of the DOD and we make space for that, and we make time for that, and we factor that into the business of the day. That’s our responsibility as a Strategic Seaport.”

Like much of America, the POA experienced a downturn in fortunes when the housing bubble burst in 2008, and the national economy went sour. “We saw a 4.1, 4.2 million tons a year volume go down to about 3.6, 3.7, and it’s slowly been creeping back since then,” Ribuffo reports. “But it hasn’t quite recovered to what it was in 2007. So in that respect, we’re in lockstep with what’s going on down in the Lower 48. But, for our market, there’s been modest growth of a percent or so a year in revenues. This year is going to be a particularly good year for us.”

When asked about the POA’s long-term strategy, Ribuffo says the following: “From a business perspective, I would like to see our revenue streams sustained and for us to grow a little bit. There’s opportunity in big, statewide, capital development projects for us to able to support, and generate a little additional revenue above what is the normal business. Alaska’s got its eye on a liquefied natural gas (LNG) pipeline construction project which is going to mean a lot of material is going to be moving into the state over about a five year period of time. They’re going to need every marine facility available to be able to keep on their scheduled timeline, and we certainly don’t want to be left out of that equation, because we’re not paying attention to what we could make available to the planners for that, now. I would like to see the Port factor prominently into those plans.”

Five decades ago, the Port of Anchorage played little brother to several other, larger maritime ports in Alaska. Today, it is the biggest player in the state. Would this transformation have happened if the Great Quake of ’64 had not occurred? While it’s hard to second-guess history, what is evidently true is that, today, the POA is an essential part of the Alaskan economy. “We are an important facility,” says Ribuffo, “and it’s going to be troublesome for the state, should something happen to it.” Certainly, it is hoped that another devastating earthquake is nowhere in Alaska’s future. But should one occur, it is also hoped that the Port of Anchorage will be ready.

______________________________________

AT A GLANCE

WHO: The Port of Anchorage

WHAT: South-Central Alaska’s main maritime seaport

WHERE: Anchorage, Alaska

WEBSITE: www.portofanc.com

PREFERRED VENDORS

Northstar Stevedores – www.northstarak.com